circa.4300

BC to 2018 AD circa.4300

BC to 2018 AD

|

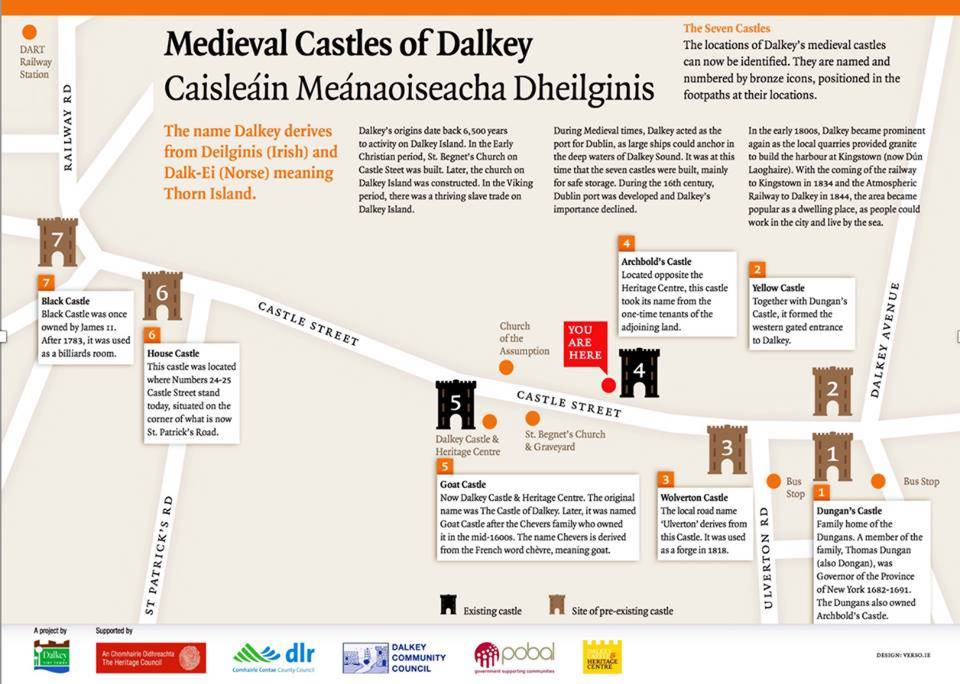

| 7 - Castles of Dalkey A Dalkey Tidy Towns Project from inception to completion |

|

See the Plaques in the pavement marking the approximate Castle locations. Map showing their Locations are at Archbolds Castle & the Dart Railway station. Dalkey

history of the Twelfth and later Centuries before & during the

time of the Castles, with some individuals having Castles named after

them . |

|

|

The original seven castles of Dalkey were built

in medieval times. In those days, Dalkey served as the port for

Dublin, when large ships could anchor and unload their cargoes in

the deep, sheltered waters of Dalkey Sound. The seven castles were

built to store goods from these ships before being transported into

Dublin city. Only two of the original seven castles remain today

– Dalkey Castle – originally called Goat Castle –

and Archbold’s Castle. |

|

Part

history of the Dalkey, during the Twelfth and later Centuries, before

and after the time of the Castles St. Begnet's Church is situated on the north side of the main street, Castle Street. It is surrounded by its churchyard, in which interments were made sporadically until the 1920's. The boundary walls are modern but the bulk of the surviving structure is Anglo-Norman.The chancel appears to have been added to a Celtic nave. The east and west windows, the belfry and, possibly, some of the entrances and other pieces of the fabric are late medieval, fifteenth or sixteenth century work. This would coincide with Dalkey's period of prosperity. The building seems to have survived into the seventeenth century but was described in Bulkeley's visitation of 1630 as ruinous with no roof on the chancel. The burgage plots may have lined both sides of the main street but there is some indication that at least one may have been parallel. They were mostly long and narrow because the site was constricted by the high rocky ground to north and south. The fields were immediately behind the burgages but the arable also extended well to the west of the town. Cottages and cabins, the dwellings of the cottiers and tenants, were interspersed among the burgages. Outside the town the commons stretched in an arc to the south and east and provided communal grazing. Peter Wilson wrote in 1768 "although this common is remarkably rocky, it nevertheless affords most excellent pasture for sheep. Here the poorer inhabitants of the town graze their cattle. Firm evidence for fortifications emerges only in the late fifteenth century. The 1482 grant of fair and market, referred to earlier, provided that the customs to be levied by the bailiff of all things and merchandises coming for sale" were to be spent on the murage and pavage of the town. There has been some suggestion that this grant was not for the benefit of Dalkey but concerned the collection of Dublin murage there. It is clear from the text of the grant, as recorded by Alen, that it related to Dalkey. In fact, it included a saver for the rights of Dublin and Drogheda. It is, indeed, hard to imagine the archbishop petitioning for a grant to benefit Dublin. Also, the date coincides with Dalkey's period of prosperity. Wilson said the town was defended on the south by a moat or ditch, which was still open. He added that the entrance to the west was through a gateway secured by two castles of which few or no traces remained. He thought the east side had also been walled. Brooking's map of the bay and harbour of Dublin, published 1728, shows Dalkey as a fortified ring, perhaps intended to indicate walls. But this may be a flight of fancy on the mapmaker's part. The walls were gone by 1770 but there may have been slight remains of the west gate. It is very difficult to discern any remains of the defences due to extensive building and, possibly, the construction of the railway. Bradley suggested, not unreasonably, that the southern rampart was co-terminous with the boundaries of the burgage plots on the south side of Castle Street. He identified a much eroded earthwork in that area. The bank is three metres high and the top is on average two metres above internal ground level. The external fosse has silted up. It is very unlikely that there stone walls which were expensive and would have been beyond the economic and manpower resources of the town. The defences would have comprised an earthen rampart, probably topped with loose rocks, and a double ditch, now filled in. There is nothing to support the idea of an earthwork on the north and, as it faced the sea and the ground was very hilly and rocky, it is quite likely that there was nothing on .that side. The existence of east and west gates predicates some form of walling on those sides, perhaps more rudimentary than the southern rampart and not extending very far in a northerly direction. There is documentary evidence for the gates. In 1565 a demise of lands to one Henry Walsh included "one cottage place or void messuage in Dalkey by the east gate of the same." This gate was probably at the end of Castle Street opposite the present Allied Irish Bank building. The conjectured market place would have been just inside the gate. In 1577 a demise to Alderman Walter Ball (which could be the same land) also mentions the east gate. The indications are that the west gate was at the junction of Barnhill Road (the old road to Dublin) and Dalkey Avenue. The road is extremely narrow at this point. All that can be said with certainty about fortifications is that there was an embankment and ditch on the south side and that there were east and west gates. There are reputed to have been seven castles, in reality fortified town houses, in Dalkey but at best only six have been identified. Bullock castle has been suggested as the seventh but that seems improbable. ( But that Information has now been clarified ) Wilson, writing in 1768, mentioned seven. He described six and the seventh had been demolished some years previously. Lewis found three in use in 1837, one as a private house, the other two as a store and a carpenter's shop. The 1843 Ordnance Survey 6 inch sheet (surveyed 1837) shows five, one to the east of the ruined church, which is clearly the Goat Castle, the present Town Hall, another site further east, a castle and a site to the west of the church and a castle on the south side of Castle Street, which is Archibold,s Castle. Two survive, the Town Hall and Archibold's. Documentary evidence for the castles is fairly good from the sixteenth century. In 1585 John Dungan, second remembrancer of the exchequer, was demised a moiety of one messuage with a castle, half an orchard and two acres of land for sixty-one years at a rental of seven shillings Irish. He was required to build up the premises, indicating that the town was in decline and the castles were deteriorating. A James Kennan got a lease of the same property for twenty-one years in 1645 at thirty shillings sterling, this lease shows the castle was on the south side of Castle Street and can reasonably be assumed to be the one now known as Archbold's Castle. The Dungans got it back at the Restoration but lost it again in the Williamite confiscations. An inquisition of 9 March 1691 stated that William Dungan, earl of Limerick, was seized of two castles, six messuages and gardens, seven acres of arable land together with meadow and pasture (seventy-four acres in total) in Dalkey. The second castle was probably on the north side of the street, where there is reasonable evidence for a Dungan's castle. An inquisition post mortem taken in 1594 showed that Henry Walshe of Killincarrig, who had died in 1570, had two castles and 75.5 acres in Dalkey, which he held of the archbishop. Another inquisition in the following year showed Robert Barnwell held another in Dalkey of the archbishop; this was described as ruinous in 1628. The fate of these Walshe and Barnwell properties in the Cromwellian and Restoration settlements is somewhat difficult to elucidate but James, duke of York (later James 11) got extensive properties at the Restoration. In 1703 John Allen of Stillorgan purchased nineteen acres in Dalkey with four castles thereon and several cabins formerly the property of King James, all for £151. Thus Dungan's two and King James's four show at least six castles in existence at the end of the seventeenth century. There was a local tradition that the seventh castle was on the south side of the street to the east of Archibold's. Some worked pieces of stone in the granite boundary walls in that area suggest that the possibility should not be ruled out. The castles built in Dalkey were fortified town houses of the late medieval period. Similar buildings have been found in places as diverse as Cork, Dingle, Dundalk, Caarlingford, Ardglass, Ardee, Termonfeckin, Newcastle Lyons, Naas and Thomastown. The Dalkey examples appear to be somewhat smaller than the norm, which may reflect smaller sites, and they were less ornamented. The builders are unknown. They were used primarily for storage and defence. Such buildings could also indicate wealth and prestige. The only families recorded as being associated with them date from the late sixteenth century. John Dungan was a merchant and government office-holder and the Barnwalls and Walshes were local gentry. While the majority of the inhabitants of Dalkey lived in much more modest dwellings, the range of fortified town houses provides material evidence of the period of prosperity enjoyed by Dalkey in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries.

INTRODUCTION

PROPERTY HOLDERS One cannot assert with any confidence that any of the persons named in the 1326 extent were associated with Dalkey town although some of the names are found there in later centuries. Dawe may be an exception. John Dawe was listed as a juror in 1326. In 1394 William Pym granted all the lands, rents and services that he had in Dalkey or elsewhere in county Dublin by the law of England in right of his late wife, Margery, to Roger Barry (or Davy?) and his wife, Margery, daughter and heiress of John Dawe and Pym.s late wife. Unfortunately, no details of the Dalkey property were given. The fact that the deed was noted in the Christ Church records suggests strongly that the property was held from the Augustinian Priory and Cathedral of Christ Church or Holy Trinity. The Dawes were a fairly important family in the manor and in the borderlands of the march. The heir of Adam Dawe, who was the king's ward, was returned manor of Shankill. Thus used to pay £2. 3s. 8d. but now paid nothing because the lands were "in malefactors" hands near the Irish.". Adam had been granted the lands in 1304. He probably succeeded his father, also names John. The archbishop was held to have alienated the land to Adam without royal licence. This seems to conflict with the view that the lands were held as pre-conquest church land free of obligations to the crown. The king apparently challenged this contention. The priory of the Holy Trinity is not mentioned in the 1326 extent but it held land in Dalkey and continued to do so into the nineteenth century. Like much else about early Dalkey, it is unclear when or how the priory acquired its interests. Archbishop Lawrence O'Toole's grants of churches and lands in 1173 did not mention Dalkey nor did the confirmation of Pope Urban111 in 1186. It is not mentioned in John's charter of 1202 in which the pre-Norman grants on the priory were recited. Archbishop Luke collated it to Holy Trinity with other churches and chapels, with all their appurtenances in chapels, lands and tithes, great and small, probably about 1240. This was confirmed by the dean and chapter of St. Patrick's Cathedral. It was usual for such grants to be confirmed by the chapters of both cathedrals but there may be an implication in this instance that it had been granted originally to St. Patrick's, possibly by Archbishop John Comyn, although there is no record of such a grant in Alen's Register nor in the "Dignitas Decani " of St. Patrick's Cathedral. To complicate matters, about 1220 there was a dispute between St, Patrick's And St. MARY'S Abbey, Dublin, about entitlement to the tithes and benefices of Clonkeen and Dalkey. St. Mary's held neighbouring Bullock and Monkstown (anciently known as Carrickbrennan), St. Patrick's renounced its claims in return for payment of half a silver mark annually by St. Mary's. Archbishop Henry had erected Clonkeen into a prebendal church of St. Patrick's about 1220 and it may be that event that brought the dispute to a head. Later this prebend was transferred to Ballymore and Lusk. How St. Patrick's still had an interest in the 1240's in unknown. Perhaps the archbishop came to an arrangement with St, Mary's and thought it desirable to join St. Patrick's in the transfer so as to remove any risk of it reviving its claims. In any event, by mid-century Christ Church was established in Dalkey and Clonkeen. It

is not known what lands originally went with St. Begnet's Church

but undoubtedly it had some. In sixteenth century leases lands on

both sides of the main street were described as ancient church land.

But the priory also obtained lands from others. Thus in 1504 Johanna

Waring, widow of Peter Bartholmew of Dublin, granted to Holy Trinity

in perpetual alms all her messuages and lands in Dalkey. The crown appears to have had a continuous interest in the Talbot properties, unlike its interest in the Dawe lands, noted earlier. This certainly challenges the accepted view that the church held all Dalkey from before the Norman conquest. It is possible that the crown lands were elsewhere in the area, Dalkey being used somewhat loosely but in absence of more information one can only pose the question. The

only surviving original grant is that of Simon Stakebull and Isabella,

his wife, to William Fox of Dalkey in 1382. A Fox was a juror in

Shankhill in the mid-thirteenth century, hiding under the Irish

form, Roger Synnuche, enquiring into allegations that the archbishop

had usurped royal prerogatives. The Stakebulls or Stakepolls were

a prominent Dublin merchant family in the fourteenth century. The

first dateable entry of one of the family in the Dublin merchant

roll is 1228-9 but there is an earlier, undated, entry, John Stakepol

was a city bailiff in 1307. He amassed considerable property in

the High Street area and died about 1334. His estate was charged

with two marks of silver for masses for his soul for thirty years.

A Robert Stakebull was mayor in 1378-9. It is possible that Simon

was a son and that the Dalkey property had been in the family for

some time. It lay between two White holdings, proof of the antiquity

of that family in Dalkey. It had been held by a John Crumpe, Robert

and Walter Crompe were in the jury that took the extent of the manor

in 1326. The

connections of marcher families such as the Dawes, Barnwalls and

Talbots with Dalkey have been mentioned. Other local gentry also

acquired property in the town, including in the sixteenth century

the Aspolls (Archbolds) and the Pippards. But the family that acquired

possibly the greatest influence were the Walshes. It was not uncommon

for a town to fall under the sway of a local lord. The earl of Ormonde

dominated Waterford and the earl of Desmond controlled Dungarvan,

Youghal, Cork and Kinsale in the late fifteenth century. As will

be seen in the next chapter, the Walshes took control of Dalkey

in the fifteenth century or came close to doing so. There were several

families of the name in the area but the ones most closely associated

with Dalkey were the Walshes of Carrickmines, county Dublin and

Killincarrig, county Wicklow. They were perceived as an unruly clan,

who seem to have adopted Irish ways. William Walshe, who had a grant

of Killiney from Holy Trinity in 1530, was known as McHowell. He

may be the William, who got a grant of lands and tithes in the area

in 1555, when he was described as son Tybbot Walshe of Carrickmines.

The dean eventually had to take legal proceedings to recover the

lands. When Henry Walshe of Killincarrig died in 1570 he held extensive

possessions in Dalkey of the archbishop and Christ Church, including

two castles and several houses. But the inquisition was not taken

until 1594, when the jury reported that "tenure of lands had

long been concealed from the Queen and her predecessors". His

son, Theobold, had taken over. In 1566 William McShane Walshe of

Corke (near Bray) was pardoned for having robbed a widow, Gormla

`O'Clondowil, in Glencullen. He was alleged to have taken a brass

pan, two gallons of butter, three sheep, a night gown, two women's

gowns and a cloak. This suggests that she was a lady of some substance

and that there was more to the affair than a simple robbery. Several

of William's kinsmen and members of other local families, Irish

and Old English, were pardoned at the same time for having rescued

him from the custody of the sub-sheriff of county Dublin. In 1602

Henry Walsh of Dalkey was pardoned for rebellion. A John Kendale is mentioned about 1326 as holding land of the prior of Holy Trinity at an annual rent of three shillings, suit of court and tolbal (a tax) of ale as often as he brewed. A person of that name was a juror in the manor of Shankhill in the same year. In 1346 the Bailiff of the priory's manor of Clonkeen bought 200 herrings from a John Kendale (the same or a relation?) for sixteen pence. When St. Mary's Abbey, Dublin, was suppressed in 1539 it held a messuage, close, and ten acres of arable in Dalkey. Most of it was leased to a John Lacy but Anthony Shillingford, Donald MacThomas and Terence Mayne each had a house without land, for which they paid an aggregate eight shillings and eight pence a year over and above the rent of two shillings due to the archbishop. Alderman Walter Ball's lease of 1577 listed his tenants, viz a messuage by the east gate on the south side of the town where John Dowling dwelt with a garden and one acre of arable; a house inhabited by William Doherty with a garden and one stang of land; the house of Dermod Riaughe with two acres and one stang of land; the house of John Owen with a garden and one stang of land, the house of MuirisMcEghy with a garden and two acres of arable; the house of the late James Rochford with a garden; the house of the late Melagh Hoper with a garden; a plot near the priest's garden and north of the churchyard. He was also required to build a house in all the waste places. Henry Walshe's lease of 1565 was equally detailed and may relate to much of the same estate. When James Kennan got his lease of Dongan's land in 1645 (Dongan was involved in the 1641 rebellion) he was required to build two houses within five years. |

|

DALKEY HOME PAGE | DALKEY COMMUNITY COUNCIL | DALKEY HERITAGE COMPANY | CANNONAID |